Understanding shortened forms

Acronyms, abbreviations and other shortened forms

There is one thing that isn’t in short supply in scientific, technical and government writing and that’s shortened forms. Whether acronyms, abbreviations, initialisms or one of several other types of shortened forms, writers often struggle to work out how to use them correctly. Let’s first look at what a shortened form is, and the different types of shortened forms. We will then explore some of the more complex issues with using shortened forms after that.

A shortened form is a compact, or contracted, representation of a word or phrase. We use these in writing to avoid re-using strings of words or expressions. This makes our writing more concise and less repetitive.

Some of the most commonly used shortened forms are contractions. Contractions can be of a single word (such as Dr, Mrs, govt, St and Cwlth) or they can be of two words (also called a grammatical contraction). Grammatical contractions include can’t, don’t, it’s and isn’t. The 6th edition of the Australian Style Manual guideline is to not use full stops at the end of single word contractions where the first and last letters of a word are used. However, if you are following another style guide, such as The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), you might use full stops (e.g. Dr., Mrs., govt., St. and Cwlth.).

Abbreviations are like single-word contractions, but they consist of only the first letter of the word, and one or more other letters, but not the last letter of the word. Examples of abbreviations include Wed., Jan., vol., i.e. and etc. Note that both the 6th edition of the Australian Style Manual and CMOS use full stops for abbreviations that end in lowercase letters.

Acronyms and initialisms consist of the initial letters of a series of words, and sometimes other letters. The difference between the two is that generally, acronyms are pronounced as a word and initialisms are not pronounced as a word. Common acronyms include WHO, NASA, laser and FedEx. Common initialisms include IRS, ATO, CD, CPA and FYI. No full stops are used in either Australian or CMOS styles for either acronyms or initialisms.

Note that some commonly used acronyms consist of upper-case and lower-case letters, or just lower-case letters (e.g. FedEx and laser). These are acronyms that have become so commonly used they are now a part of standard language. However, they maintain a capital letter if they are a proper name, such as Nasdaq.

Some words could be considered either an acronym or an initialism, depending on whether the user pronounces it as one word or not. Common social media shortened forms often fit into this category, such as lol and yolo.

Lastly, symbols are considered a shortened form. Symbols may consist of either a non-alphabetic representation (such as $ and %) or an alphabetic representation (such as m (metre), lb. (pound) and Au (gold)).

Alphabetic symbols that represent Système international d’unités (SI) units (such as km for kilometre) do not take a full stop, but alphabetic symbols representing Imperial/US units of measure (such as mi. for mile) generally do take a full stop.

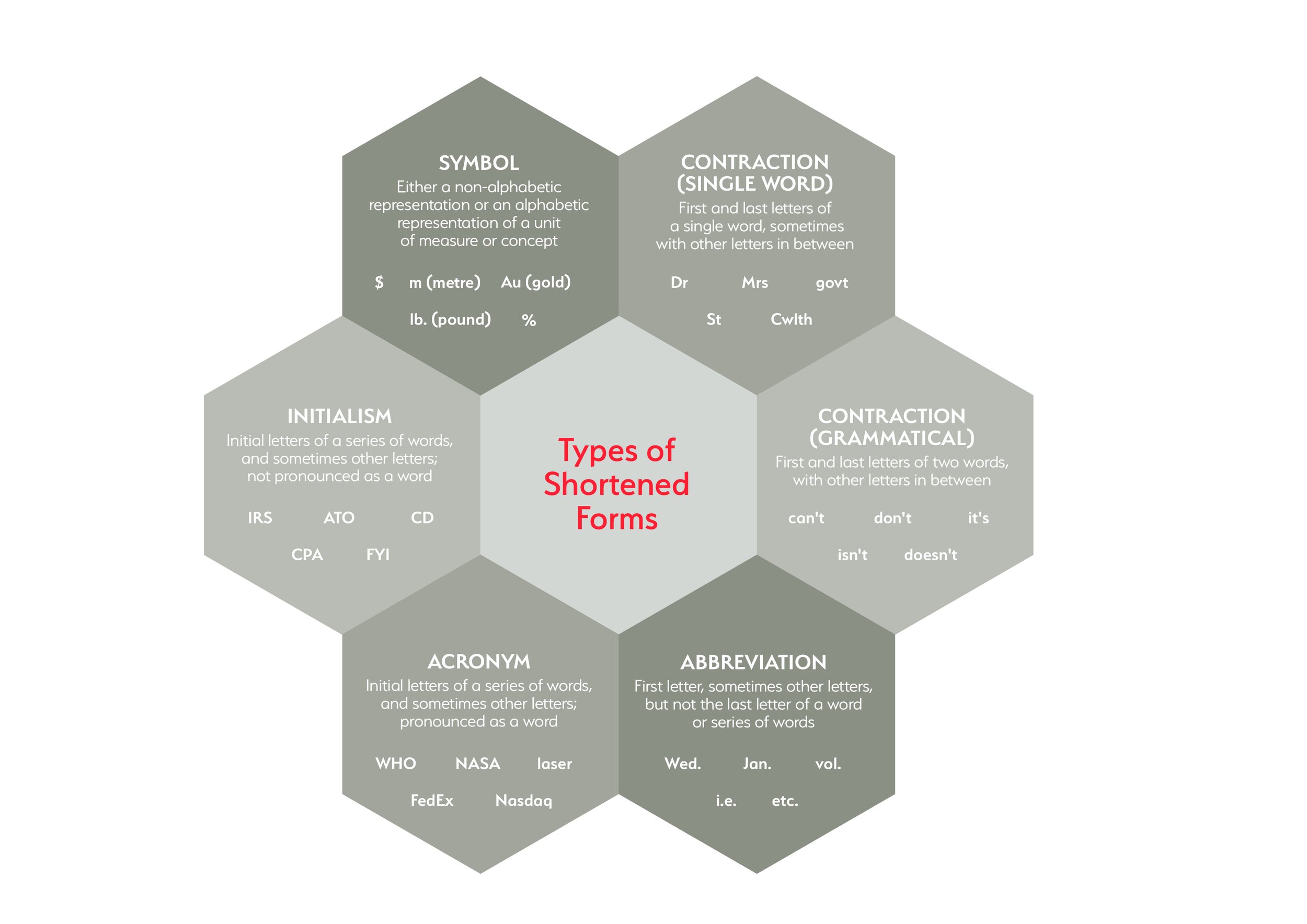

This diagram is a quick summary of the differences between the different types of shortened forms.

While shortened forms can help make your writing concise, take care not to confuse readers when using them.

The general rule is that shortened forms (abbreviations, acronyms, initialisms and sometimes symbols) should be spelled out in full at their first use, with the shortened form afterwards in parentheses. The shortened form can then be used afterwards. In larger documents, however, it might be useful to spell out shortened forms at first use in each section or chapter to remind an unfamiliar audience of what the terms mean. Inclusion of a glossary or list of shortened forms is also recommended.

There are some disadvantages to using shortened forms. For instance, in a technical article to be read by a nontechnical audience, use of a lot of shortened forms may make the writing difficult to read. Also consider whether a shortened form is really necessary, especially if the term is only used once or twice in the piece of writing.

Many authors find differentiating between a plural and a possessive form of a shortened form difficult. A plural shortened form uses just the letter ‘s’ at the end, such as ‘five CDs’ and ‘two TVs’. A possessive shortened form uses an apostrophe and the letter ‘s’ at the end, such as:

FedEx’s website

ATO’s ruling

WHO’s policy.

Another confusing aspect of shortened forms is whether they act as singular or plural. For example, consider the two sentences:

GCL was listed on the Australian Stock Exchange yesterday.

GCL were listed on the Australian Stock Exchange yesterday.

Because GCL is a single entity, it should generally be considered singular, as in ‘GCL was listed …’. However, there are some exceptions to this rule, so if you would like to know more, have a look at my blog on subject–verb agreement for corporate entities.